Riding the Marry-Go-Round

I’m a two-timer. An encore performer. A twin-biller. A mulligan-taker. A repeat customer. A re-doer. A rider on the marry-go-round. I’m remarried.

I was remarried at 47, placing me among the 16 percent of U.S. men aged 40 to 49 who have been married twice, a figure that climbs to 21.6 percent at 50 to 59 and to 24.6  percent, or nearly 1 out of every 4 men, at 60 to 69, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2015 study, “Remarriage in the United States.” An even higher percentage of 40-to-49-year-old females, 18.2 percent, have been married twice.

percent, or nearly 1 out of every 4 men, at 60 to 69, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2015 study, “Remarriage in the United States.” An even higher percentage of 40-to-49-year-old females, 18.2 percent, have been married twice.

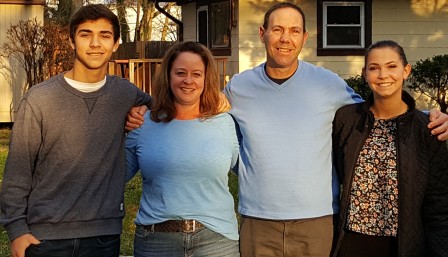

My second wife has watched my two kids, who are now college-aged young adults, grow up since they were 9 and 7, and became their stepmother when they were 14 and 12, heading into the most challenging adolescent years. It requires bravery, patience, tolerance, acceptance, respect, understanding, flexibility, persistence, discipline, forgiveness and the capacity to love to become an effective and enduring stepparent.

Remarriage brings a whole new set of complications and negotiations for the new couple that cause stress: blended families; ex-spouses who may be intrusive; divided loyalties among children and extended family members; ambiguous stepparent roles and expectations; uncertain and evolving children’s reactions to changing family dynamics; financial complexities; practical and logistical decisions to reconcile often well-established, separate lives, lifestyles and cultures; trust issues and other emotional baggage; and legal agreements and bleed-over contentiousness from first marriages. Compared to the virtual blank slate of a first marriage, remarriage can appear an Etch A Sketch on steroids. My second marriage has not been immune from some of these challenges.

If raising kids is the toughest job you could ever have, imagine stepping in as a relief pitcher in the seventh inning, when kids are entering and navigating adolescence as mine were, with all the challenges that raging hormones, establishing independent identities, questioning authority and fitting in with peers presents. A stepparent who adopts an authoritarian approach risks creating an environment of constant tension and turmoil.

On the matter of step-parenting, The Gottman Institute, which researches marriage and relationships, explains the disappointment a stepparent encounters in desiring reciprocal love from stepchildren that may fall short of expectations, and outlines a realistic role: The “role of the stepparent is one of an adult friend, mentor, and supporter rather than a disciplinarian,” says the Gottman Institute blog. “There’s no such thing as instant love. When stepparents feel unappreciated or disrespected by their stepchildren, they will have difficulty bonding with them – causing stress for the stepfamily.”

When a biological parent of the same gender as the stepparent is firmly involved in the family picture and the children’s lives, even when not living with them full-time, it may be unrealistic to expect of the children to show equal respect, appreciation and love to each parental figure. A stepparent who keeps score in such ways is setting himself or herself up for disappointment, corrosive resentment and an emotional rollercoaster ride. Children of divorce do their best to cope with confusing and distressing situations and want nothing to do with choosing sides or participating in competitions for their attention and affection, even under the friendliest of circumstances.

Financial issues, which can be vexing in first marriages, can become even more complicated in second marriages. Sharing finances and deciding on financial priorities are aspects of marriage that can produce vulnerability and distrust. These feelings can be amplified in remarriage when one or both partners, often with decades of accumulated assets, debts and obligations, may have children for whom they are financially responsible, child support or alimony payment arrangements, pending college tuition and room and board costs, or property, equity and retirement investments. My second wife married me at a time when I had years of kids’ college costs upcoming. In any remarriage, it would be fair to ask: What should be the new stepparent’s financial obligation toward the stepchildren’s college expenses, if any?

Remarriage is volatile. The odds of second marriages surviving are worse than first marriages. The National Stepfamily Resource Center cites a divorce rate among individuals who get remarried of 60 percent, while most measures of the divorce rate among first-timers hover around 50 percent. Studies show those who have experienced divorce before are more likely to consider it again when marital struggles emerge. Also, ex-spouse conflicts and new partners parachuting into often ill-defined parenting responsibilities add to the strain that pushes the remarriage divorce rate higher.

Yet those who have lost in love still want to take their mulligans, men more than women. A 2014 Pew Research Center study found that adults who have been previously married are more likely than not to remarry: 57 percent of previously married 35-to-44-year-olds; 63 percent of 45-to-54-year-olds; and 67 percent of 55-to-64-year-olds had remarried. A Pew survey found that only 30 percent of previously married men did not want to remarry, while 54 percent of previously married women indicated they would prefer to remain single, reflecting men’s greater needs for the social and emotional support that marriage provides.

Perhaps more than anything, the high rates of remarriage show resiliency of spirit, faith in the institution and the innate desire of humans to connect on a deeper level and share lives, longings that outweigh the challenges of remarriage for many. Apparently, remarriage stands as the poster child for the trite cliché: “If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again.”

burying the hurt, anger, disappointment, sadness or other negative emotions until one day they boil over and surface in a torrent, providing release for the emotional-baggage carrier and a knockdown punch for the recipient of the pent-up emotions, unaware of the depth and intensity of feelings. I’ve been on both the unleashing and receiving ends of the bubbling emotional volcanos, and it’s never pretty.

burying the hurt, anger, disappointment, sadness or other negative emotions until one day they boil over and surface in a torrent, providing release for the emotional-baggage carrier and a knockdown punch for the recipient of the pent-up emotions, unaware of the depth and intensity of feelings. I’ve been on both the unleashing and receiving ends of the bubbling emotional volcanos, and it’s never pretty. assignment teaching English in two French middle schools, her first professional job after graduating college. This will be her second tour abroad, following a semester in college in which she studied at the University of Lyon in Lyon, France, and traveled throughout Europe.

assignment teaching English in two French middle schools, her first professional job after graduating college. This will be her second tour abroad, following a semester in college in which she studied at the University of Lyon in Lyon, France, and traveled throughout Europe. presence with materials, she was saying.

presence with materials, she was saying. himself from the masses who hold college degrees, which no longer guarantee entry into the professional world, by going the STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Math) route and will find himself in demand in the job market. No post-college Parental Unit Domicile (PUD) basement-dwelling likely or necessary for him!

himself from the masses who hold college degrees, which no longer guarantee entry into the professional world, by going the STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Math) route and will find himself in demand in the job market. No post-college Parental Unit Domicile (PUD) basement-dwelling likely or necessary for him!

What are the odds that a father and a daughter would graduate from different universities on the same day?

What are the odds that a father and a daughter would graduate from different universities on the same day? have, always seeking, never arriving. Or it can be the motivation that leads to risk-taking, improvement and growth.

have, always seeking, never arriving. Or it can be the motivation that leads to risk-taking, improvement and growth.

my 20-year-old daughter and high school graduate son perfect or devoid of flaws or insecurities. Neither are your classic All-Americans or stereotypical overachievers. But they are on good tracks in their lives, have done quite well for themselves, and, importantly for me, rarely caused me any worry, grief or stress that more troubled children can cause parents.

my 20-year-old daughter and high school graduate son perfect or devoid of flaws or insecurities. Neither are your classic All-Americans or stereotypical overachievers. But they are on good tracks in their lives, have done quite well for themselves, and, importantly for me, rarely caused me any worry, grief or stress that more troubled children can cause parents.