Listening

A follow up to my post on Facing the Music (from May 17, 2017, re-posted below), describing my invitation to have an authentic conversation with my young adult daughter Rebecca to hear her perspective on growing up in a family of divorce and the mistakes or oversights I may have made during those crucial years of development:

Time was running short, but I didn’t want to be a typical “all talk, no do” phony dad. I made my overture for an honest conversation just before I went to the beach for three months to teach tennis. Now I had less than two weeks back home until Rebecca traveled to France for a school year to teach English, and she was busy preparing and doing things with friends and family.

There seems never a good time to have difficult, uncomfortable and potentially distressing conversations. They’re easily avoided, and that’s what many people do,  burying the hurt, anger, disappointment, sadness or other negative emotions until one day they boil over and surface in a torrent, providing release for the emotional-baggage carrier and a knockdown punch for the recipient of the pent-up emotions, unaware of the depth and intensity of feelings. I’ve been on both the unleashing and receiving ends of the bubbling emotional volcanos, and it’s never pretty.

burying the hurt, anger, disappointment, sadness or other negative emotions until one day they boil over and surface in a torrent, providing release for the emotional-baggage carrier and a knockdown punch for the recipient of the pent-up emotions, unaware of the depth and intensity of feelings. I’ve been on both the unleashing and receiving ends of the bubbling emotional volcanos, and it’s never pretty.

A few days before Rebecca jetted off, we found ourselves together at home, and I broached the topic. Understandably, Rebecca was ambivalent about getting into an emotional conversation about past wounds and frustrations before embarking on an adventure of a lifetime. But she started talking, and I listened and asked questions.

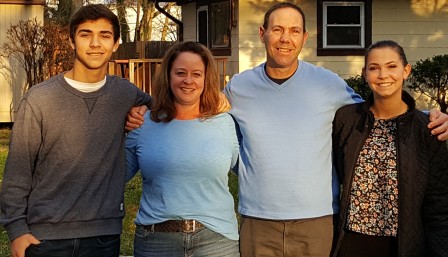

I can’t reveal the content of what we discussed about our relationship and family life, and the complications and challenges Rebecca faced as a child, along with her younger brother, whose parents separated 12 years ago when she was 9 and ultimately divorced. It’s too private.

But I can say that at certain times I could have handled things better, that I was caught up in myself, that I made some mistakes, and that I was sometimes unaware of – or didn’t want to acknowledge – how much the kids observed, heard, knew or perceived, even at relatively young ages. Listening to Rebecca’s perspective and looking back, I can say how challenging it was for me to balance the needs, feelings, happiness, stability and security of my kids with my own needs, desires and emotions, and to try to lean toward selfless rather than selfish.

Divorce and eventual remarriage created some circumstances that ultimately were going to cause some distress for Rebecca individually and in our relationship, no matter what I did or said. The complexities of a marriage breakup and the constantly evolving aftermath can’t be fully grasped by a child, whose experience can be like that of a pinball ricocheting within a constrained environment. I experienced the pinball game as a child, and certainly didn’t understand everything that was going on with my divorced parents, and now so has Rebecca.

The beauty of our conversation was that Rebecca was able to tell me some things about what transpired from her perspective, what she experienced and how she felt honestly, and I was able to listen while squelching the default tendency to be defensive or critical.

We got through it with our relationship intact and expressions of love for each other. I’m hoping our conversation helps set a foundation for our future adult relationship, one in which we can be open and honest with each other without fear that we will be jeopardizing our relationship by revealing our feelings and with knowledge that we love each other unconditionally regardless of any conflicts, hurt feelings or differences that can be addressed and resolved.

So many relationships between fathers and adult children barely break the surface because of the dread of churning what lies beneath and what digging will uncover, or because of an inability, unwillingness or lack of desire to go deeper. Stoicism and emotional avoidance are drilled into males. I don’t want that type of relationship with my kids as they grow into adulthood. I want them to know and understand me, with all my attributes and faults, as I do them. I want us to be able to know and share our emotional selves. The only way to do that is to be emotionally available and vulnerable to them, and to show that I care about and want to know how they feel, and can handle it when they lay it on me.

One takeaway from our conversation is that whatever mistakes I made as Rebecca was growing up, I believe that she accepts my apologies, forgives my transgressions, acknowledges that I have tried to be a good and caring father and doesn’t expect me to be perfect. Our conversation was a good start toward setting the standard and expectation of our relationship for the future. I’m glad we each took the risk of having it instead of avoiding it.

Facing the Music (Midlife Dude Blog Post from May 17, 2017)

As my daughter Rebecca and I were discussing her sociology class on adolescence, she tangentially announced, “You and mom did a good job raising me.”

Surprised by an out-of-the-blue compliment, I asked, “What makes you say that?”

Rebecca explained that she does not view herself as materialistic, implying instead that she values experiences and relationships above things. We provided for her needs and many wants, but we didn’t overindulge, and didn’t replace our caring, attention and presence with materials, she was saying.

As a 21-year-old sociology major graduating from the University of Maryland in four days, she has learned about inequality, justice, race, poverty, privilege, human development and other similar topics, helping her become more insightful and introspective about her own life, and more astute about distinctions among individuals and communities.

I was happy to hear Rebecca praise our parenting, since her mom and I broke up when she was 9. My biggest fear about our divorce was that it would cause emotional and psychological problems for Rebecca and younger brother Daniel.

“So we did a lot of things right,” I said, fishing for more praise.

“Yeah, but not everything,” she said, adding the inevitable disclaimer.

“What didn’t we do so well?”

“There were things I haven’t talked to you about.”

We were headed to an Easter celebration, so there wasn’t time, and it wasn’t the right time, to get below the surface. But I kept the conversation in my memory, committed to return to it.

I did that last weekend, inviting Rebecca to have an open discussion with me as a young adult, reflecting on her experiences as a pre-teen and teenager, the positive and the negative, the gratifying and the disappointing, the supportive and the hurtful.

That conversation, I recognize, will require certain things of me, to be constructive rather than destructive or dismissive: I’ll want to approach it as a listener, not a talker, and with an open-minded, non-judgmental, non-defensive attitude. Because I know my temptation, like any parent told in retrospect they weren’t as magnificent as they believed, will be to explain or justify or rationalize or correct the record, which would only serve to shut down Rebecca, diminish openness, trust and honesty and invalidate her experiences and feelings. My current training in counseling should help me control such urges.

I would like to give Rebecca the chance to have an open forum with me without fear of reprisal or disengagement. I believe it’s important to transition into our adult relationship with everything in the open, past issues revealed and understood, nothing left unsaid, as the foundation for our future interactions and communications. It’s the key to an emotionally healthy, genuine father-daughter relationship.

I don’t know what she will say to me. I don’t know if I’ll be surprised. I don’t know what emotions it will trigger. But I want to hear it. I know I had good intentions throughout her childhood, and did my best as a father. But I also know I made mistakes. And I know the fact of divorce created situations and triggered emotions that were difficult, or perhaps impossible, to manage without having an impact on the kids.

Facing the music about my role and impact as a divorced (and remarried) father in my daughter’s life will increase my awareness and, I hope, strengthen my ability to relate to Rebecca. It’s worth whatever discomfort or ego deflation it may cause me.

assignment teaching English in two French middle schools, her first professional job after graduating college. This will be her second tour abroad, following a semester in college in which she studied at the University of Lyon in Lyon, France, and traveled throughout Europe.

assignment teaching English in two French middle schools, her first professional job after graduating college. This will be her second tour abroad, following a semester in college in which she studied at the University of Lyon in Lyon, France, and traveled throughout Europe. was only for other people who marry the wrong person, have poor character or morals, or can’t figure out how to make a marriage work, only to end up immersed in the previously unthinkable, bewildered by how such a good thing could have turned so unpleasant.

was only for other people who marry the wrong person, have poor character or morals, or can’t figure out how to make a marriage work, only to end up immersed in the previously unthinkable, bewildered by how such a good thing could have turned so unpleasant. presence with materials, she was saying.

presence with materials, she was saying.

At neighborhood events, I often see my former guitar teacher, my neighbor who has a guitar studio within walking distance where I once took lessons. And then, inevitably, a wave of regret and guilt washes over me.

At neighborhood events, I often see my former guitar teacher, my neighbor who has a guitar studio within walking distance where I once took lessons. And then, inevitably, a wave of regret and guilt washes over me. himself from the masses who hold college degrees, which no longer guarantee entry into the professional world, by going the STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Math) route and will find himself in demand in the job market. No post-college Parental Unit Domicile (PUD) basement-dwelling likely or necessary for him!

himself from the masses who hold college degrees, which no longer guarantee entry into the professional world, by going the STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Math) route and will find himself in demand in the job market. No post-college Parental Unit Domicile (PUD) basement-dwelling likely or necessary for him!

What are the odds that a father and a daughter would graduate from different universities on the same day?

What are the odds that a father and a daughter would graduate from different universities on the same day?